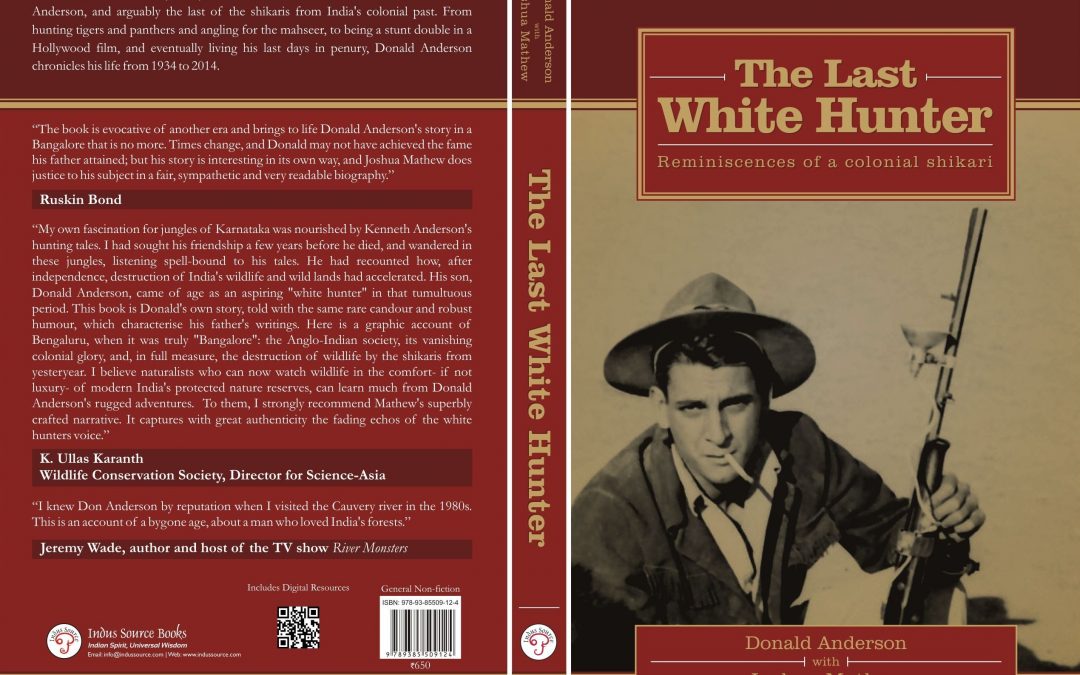

New Book: Donald Anderson with Joshua Matthew, The Last White Hunter: Reminiscences of a colonial shikari (Indus Source Books)

Although the Crown Rule or British Raj is defined from the years 1858 to 1947, Britain’s association with India started centuries earlier. The British East Indies company began trade along the coasts of India from the early 1600s, competing with the Dutch and the French to gain access to an abundance of natural resources in India. In 1757, when Robert Clive won the Battle of Plassey, the incident often considered the beginning of the British Empire in India, Scotland was already a part of Great Britain. And among the multitude of people who crossed the Cape of Good Hope to come to India, the Scots constituted a sizeable population. Those who landed on Indian shores were an eclectic mix of civil servants, traders, missionaries, army men, teachers, all seeking adventure, fame or fortune in one form or another. The domiciled British came to be known as Anglo Indians, although over the course of the next two centuries, the definition would change many times over. For the new migrants, especially among the men who lived in proximity to forests, hunting provided not just recreation, but also a rite of passage.

Conservation was unheard of, and tigers, panthers, bears and other mega fauna were often considered vermin and hunters were rewarded for their destruction.

However, the early hunters all hunted for sport, and not until Jim Corbett ‘s book ‘Man-eaters of Kumaon’ in 1944, did the colonial shikari’s tales garner mass appeal. Corbett was born in India and while a pucca sahib at heart, his love for India and the people were genuine and there was a certain Indian-ness that transpired in his books. Kenneth Anderson was his equivalent in south India. His ancestors arrived in India in the early 1800s from Glasgow and his father, who worked for the Army, settled down in Bangalore. Kenneth wrote 8 books, that were not about hunting for sport like the early settlers, but putting an end to man eating tigers and panthers that were a menace to society. After independence, Kenneth decided to stay on in India and he passed away in 1974. His son, Donald who considered himself a ‘white hunter’ lived a colourful life, witnessing an incredible transformation in the world around him, from 1934 to 2014. I’ve tried to reconstruct his incredible, poignant and ultimately wretched story over those years.

I believe that Donald’s story of adventure and fun, yet of hardship and loss would appeal to many Anglo-Indians especially those who still remember growing up in India. His tale is rather unique in a sense too, because he witnessed life in both British and independent India and his story provides so many perspectives of life over 80 transformational years.